Leading The way forward

The Paris Agreement

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change

Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs)

The Paris Agreement’s aim is to strengthen the global response to the threat of climate change by keeping a global temperature rise this century well below 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels and to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase even further to 1.5 degrees Celsius. Additionally, the agreement aims to strength

The Paris Agreement’s aim is to strengthen the global response to the threat of climate change by keeping a global temperature rise this century well below 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels and to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase even further to 1.5 degrees Celsius. Additionally, the agreement aims to strengthen the ability of countries to deal with the impacts of climate change. To reach these ambitious goals, appropriate financial flows, a new technology framework and an enhanced capacity building framework will be put in place, thus supporting action by developing countries and the most vulnerable countries, in line with their own national objectives. The Agreement also provides for enhanced transparency of action and support through a more robust transparency framework. There will be a global stocktake every 5 years to assess the collective progress towards achieving the purpose of the Agreement and to inform further individual actions by Parties.

Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs)

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change

Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs)

Nationally determined contributions (NDCs) are at the heart of the Paris Agreement and the achievement of these long-term goals. NDCs embody efforts by each country to reduce national emissions and adapt to the impacts of climate change. The Paris Agreement (Article 4, paragraph 2) requires each Party to prepare, communicate and maintain

Nationally determined contributions (NDCs) are at the heart of the Paris Agreement and the achievement of these long-term goals. NDCs embody efforts by each country to reduce national emissions and adapt to the impacts of climate change. The Paris Agreement (Article 4, paragraph 2) requires each Party to prepare, communicate and maintain successive nationally determined contributions (NDCs) that it intends to achieve. Parties shall pursue domestic mitigation measures, with the aim of achieving the objectives of such contributions.

The Paris Agreement requests each country to outline and communicate their post-2020 climate actions, known as their Nationally Determined Contributions.

Together, these climate actions determine whether the world achieves the long-term goals of the Paris Agreement and to reach global peaking of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions as soon as possible and to undertake rapid reductions thereafter in accordance with best available science, so as to achieve a balance between anthropogenic emissions by sources and removals by sinks of GHGs in the second half of this century.

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change is an international environmental treaty adopted on 9 May 1992 and opened for signature at the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro from 3 to 14 June 1992. Today, it has near-universal membership. The 197 countries that have ratified the Convention are called Parties to the Convention.

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change is an international environmental treaty adopted on 9 May 1992 and opened for signature at the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro from 3 to 14 June 1992. Today, it has near-universal membership. The 197 countries that have ratified the Convention are called Parties to the Convention. Preventing “dangerous” human interference with the climate system is the ultimate aim of the UNFCCC.

Carbon Trading Explained

Click on the Video Link

the paris agreement

The kyoto protocol

What Is The Carbon Market

Emissions Trading

Global "Stock Market"

The Kyoto Protocol

The Carbon Market - The limits on greenhouse-gas emissions set by the Kyoto Protocol are a way of assigning monetary value to the earth's shared atmosphere -- something that has been missing up to now. Nations that have contributed the most to global warming have tended to benefit directly in terms of greater business profits and higher standards of living, while they have not been held proportionately accountable for the damages caused by their emissions. The negative effects of climate change will be felt all over the world, and actually the consequences are expected to be most severe in least-developed nations which have produced few emissions.

The Kyoto Protocol

Global "Stock Market"

The Kyoto Protocol

The Kyoto Protocol is an international agreement linked to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, which commits its Parties by setting internationally binding emission reduction targets. Individual industrialized countries will have mandatory emissions targets they must meet. . . but it is understood that some will do better than expected, coming in under their limits, while others will exceed them.

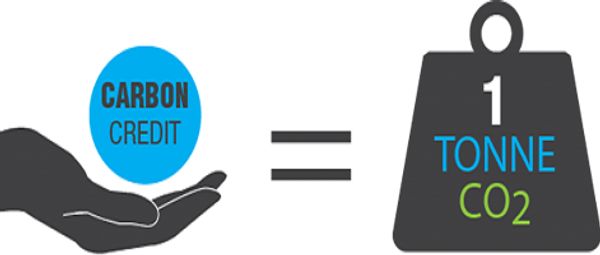

The Protocol allows countries that have emissions units to spare -- emissions permitted them but not "used" -- to sell this excess capacity to countries that are over their targets. This so-called "carbon market" -- so-named because carbon dioxide is the most widely produced greenhouse gas, and because emissions of other greenhouse gases will be recorded and counted in terms of their "carbon dioxide equivalents" -- is both flexible and realistic. Countries not meeting their commitments will be able to "buy" compliance. . . but the price may be steep. The higher the cost, the more pressure they will feel to use energy more efficiently and to research and promote the development of alternative sources of energy that have low or no emissions.

Global "Stock Market"

Global "Stock Market"

Global "Stock Market"

A global "stock market" where emissions units are bought and sold is simple in concept -- but in practice the Protocol's emissions-trading system has been complicated to set up. The details, weren't specified in the Protocol, and so additional negotiations were held to hammer them out. These rules were among the workaday specifics included in the 2001 "Marrakesh Accords." The problems are clear: countries' actual emissions have to be monitored and guaranteed to be what they are reported to be; and precise records have to be kept of the trades carried out. Accordingly, "registries"-- like bank accounts of a nation's emissions units -- are being set up, along with "accounting procedures," an "international transactions log," and "expert review teams" to police compliance.

More than actual emissions units will be involved in trades and sales. Countries will get credit for reducing greenhouse-gas totals by planting or expanding forests ("removal units"); for carrying out "joint implementation projects" with other developed countries, usually countries with "transition economies"; and for projects under the Protocol's Clean Development Mechanism, which involves funding activities to reduce emissions by developing nations. Credits earned this way may be bought and sold in the emissions market or "banked" for future use.

cdm explained and monitoring form